Posts

Showing posts from 2022

When people suggest topics for me to write about, more often than not I can point to an article I’ve already written, which is handy for me. I doubt I’ll ever run out of thoughts on new topics, but it’s good to have a body of work to refer to. Here are my posts for the past two weeks: Car Companies Complaining about Interest Rates RRSP Confusion Searching for a Safe Withdrawal Rate: the Effect of Sampling Block Size Here are some short takes and some weekend reading: Ben Carlson lists some things in the markets that surprised him this year. The first thing is that stocks and bonds both went down double-digits. Apparently, that’s never happened before. I guess if you just look at the history of stock and bond returns, this outcome looks surprising. However, when you look at the conditions we’ve come through, this was one among a handful of likely outcomes. Bond markets were being artificially propped up, and the dam had to burst sometime. As for...

Searching for a Safe Withdrawal Rate: the Effect of Sampling Block Size

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

How much can we spend from a portfolio each year in retirement? An early answer to this question came from William Bengen and became known as the 4% rule . Recently, Ben Felix reported on research showing that it’s more sensible to use a 2.7% rule . Here, I examine how a seemingly minor detail, the size of the sampling blocks of stock and bond returns, affects the final conclusion of the safe withdrawal percentage. It turns out to make a significant difference. In my usual style, I will try to make my explanations understandable to non-specialists. The research Bengen’s original 4% rule was based on U.S. stock and bond returns for Americans retiring between 1926 and 1976. He determined that if these hypothetical retirees invested 50-75% in stocks and the rest in bonds, they could spend 4% of their portfolios in their first year of retirement and increase this dollar amount with inflation each year, and they wouldn’t run out of money within 30 years. R...

RRSP Confusion

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Recently, I was helping a young person with his first ever RRSP contribution, and this made me think it’s a good time to explain a confusing part of the RRSP rules: contributions in January and February. Reader Chris Reed understands this topic well, and he suggested that an explanation would be useful for the upcoming RRSP season. Contributions and deductions are separate steps We tend to think of RRSP contributions and deductions as parts of the same set of steps, but they don’t have to be. For example, if you have RRSP room, you can make a contribution now and take the corresponding tax deduction off your income in some future year. An important note from Brin in the comment section below: “you have to *report* the contribution when filing your taxes even if you’ve decided not to use the deduction until later. It’s not like charitable donations, where if you’re saving a donation credit for next year you don’t say anything about it this year.” Most of the time, people t...

Car Companies Complaining about Interest Rates

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

I don’t often have much to say about macroeconomic issues, but an article “sounding the alarm” about how interest rate increases are affecting car companies drew a reaction. “Aggressively raising interest rates has helped create an untenable situation in car financing.” Good. Financing a car is usually a mistake for the consumer. When consumers’ credit is so bad that they can’t even get a car loan, it’s even clearer that they shouldn’t buy the car. “The auto sector is one of the victims of the aggressive interest rate hikes.” Ridiculously low interest rates have allowed car companies to inflate prices and sell ever more cars to people who can’t really afford them. The fact that the party is ending doesn’t make car companies victims. Conditions are just slowly getting back to normal. “Rising interest rates will make consumers reevaluate their decisions before quickly jumping into a car loan.” Good. It’s sad when people bury their financial future by buying ...

Short Takes: U.S. Equity ETFs, Index Investing Advantage, and more

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

There’s a whole world of retired people who play sports that I didn’t know existed until the last few years. As I aged and was trying to compete with much younger athletes, I often wondered how much longer I could keep going. A common mindset among older players is that they’ll have to give it up sometime, probably soon. However, when I play sports with people my age and older, I see that I can keep going as long as I can stay healthy enough. Rather than focusing on how much physical ability I’ve lost, I can focus on finding people who play at roughly the same level I do. This has increased my motivation to do targeted exercise to keep my body healthy enough to play sports. You’d think that staying healthy and strong would be motivation enough, but I find the deadline of completing rehab before an upcoming sports season much more motivating. Here are some short takes and some weekend reading: Justin Bender compares U.S. stock ETFs domiciled in Canada (e.g....

Short Takes: Bond Debacle, FTX Debacle, and more

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

It’s no secret that bonds got crushed this year as interest rates rose. Rob Carrick went so far as to say “Given how absurdly low rates were in 2020 and 2021, your adviser should have seen the events of 2022 [the bond crash] coming.” I agree in the sense that the bond crash was predictable, but its exact timing was not. I explained the problem with long-term bonds back when there was still time to avoid the losses . It’s important to be clear that I was not making a bond market prediction. What was certain was that long-term bonds purchased in 2020 were going to perform very poorly over their lifetimes. The exact timing of bond losses was not knowable with any certainty. The tight coupling between interest rates and bond returns is what made it possible to see the brewing problems; this isn’t possible with stocks. I’ve seen a few attempts by financial advisors to justify their failure to act for their clients by talking about how if you blend poor lon...

Quit: The Power of Knowing When to Walk Away

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Former professional poker player and author of Thinking in Bets , Annie Duke has another interesting book called Quit: The Power of Knowing When to Walk Away . Through entertaining stories and discussion of scientific research, she makes a strong case that people aren’t good at deciding when to quit relationships, jobs, and many types of life goals. In one interesting story, “Blockbuster, when presented with the opportunity to acquire Netflix, refused.” We now know that Blockbuster would have been better off focusing on streaming and giving up on renting physical copies of movies. Of course, if they had tried to do both, their own executives responsible for renting movies might have killed off streaming to protect their own jobs and bonuses. Other interesting and tragic stories concern those who failed to give up on climbing Mount Everest when it became too dangerous, and the many people who have finished marathons on broken bones “ Because there’s a finish line ” they...

When Small Fees Equate to High Interest Rates

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

There are many ways to hide banking fees so that customers don’t notice them. One way is to quietly help yourself to a couple percent of people’s mutual fund savings every year. Another is to tack a foreign exchange fee onto the exchange rate when customers exchange currencies. I learned about a new one recently with credit card payment plans. Many of the big banks offer plans that allow you to take a credit card purchase and pay it off over 6 months to 2 years at a low-sounding interest rate. The trick is that they add fees that also seem small, but they add up. One example is TD’s credit card payment plan that allows you to pay for large purchases over 6 months at zero percent interest for a one-time fee of 4%. This sounds way better than paying standard credit card interest rates. However, looks can be deceiving. Suppose you make a $600 purchase. With the 4% fee, this grows to $624. At 0% interest, you could use the payment plan to pay ...

Short Takes: FTX Debacle and Foreign Withholding Taxes

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

It’s amazing how trivial it is to invest well, and yet we need to know a lot to be able to avoid changing course to some inferior strategy that sounds good but isn’t. I did poorly with my own portfolio for about a decade before smartening up, and I’ve done well for my mother, sister, and mother-in-law, but I haven’t been able to help most others who ask for advice. In most cases, I end up watching helplessly as they make choices with poor odds. It would be easier if saying “just buy VBAL” were persuasive. Here is my review of a book on homeownership: House Poor No More Here are some short takes and some weekend reading: Marc Cohodes holds nothing back in his analysis of Sam Bankman-Fried and FTX. I doubted that I’d end up listening to the entire podcast, but I couldn’t stop once I started. Justin Bender explains U.S. foreign withholding taxes (FWT) on various types of ETFs that hold U.S. stocks. This is an important topic, because FWT on dividends can be ...

House Poor No More

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Romana King’s book House Poor No More is a comprehensive collection of useful knowledge for all aspects of owning a home, including detailed lists of home maintenance tasks, improvement projects, and much more. The writing is upbeat and engaging. To the author’s credit, she quantifies the costs of just about everything. Unfortunately, this book was written just before interest rates shot up, so several numerical examples look like they are from the “before times” (only 9 months ago). As has been common in our society for many years now, the author is too positive about taking on large debts. Those who took on far too much debt while ignoring the possibility of interest rate increases are now facing significant pain. Some Positives As a long time homeowner, I thought I had a good handle on home maintenance. However, King’s comprehensive list of home maintenance tasks covers many areas I know little about. The many things to check and possibly re...

Short Takes: $340k Phone Hack, Harsh Investment Lessons, and more

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Early this year I got a new U.S. dollar credit card but had a hard time getting a reasonable credit limit. After some trouble, I managed to get the bank to increase the credit limit a little. This week I got a popup after logging in to my online banking telling me I was pre-approved for another US$4000 increase. This happened shortly after I had maxed out the card and then paid it off. I guess they just wanted to see more of a track record on this card before upping the limit, even though I already have a multi-decade track record with another credit card at the same bank. I was amused when I clicked to accept the pre-approved credit limit increase and got a message saying that they would let me know whether they would “approve my request.” Later, another automated message congratulated me on getting “my request” for a higher credit limit approved. What I’d like to know is how often these “pre-approved” credit limit increases get rejected. Here ...

Short Takes: Homeowner Insolvencies, CRA Flouting Court Rules, and more

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

It’s a strange feeling to watch the beginning of the carnage in the housing market and know that it must get much worse if my sons are to have a chance to buy a home for a price they can afford. Here are my posts for the past two weeks: The Inevitable Masquerading as the Unexpected Inflation Porn Here are some short takes and some weekend reading: Doug Hoyes explains why he does “not expect a significant rise in homeowner insolvencies until mid- to late-2023.” A judge has ruled against CRA in three appeals of gross negligence penalties, not based on the merits of the cases, but because of CRA’s “egregious” behaviour . From the judge’s ruling, it seems that CRA is willing to flagrantly violate court rules in cases where they believe taxpayers are guilty of gross negligence. A powerful government agency such as CRA has no business engaging in such gamesmanship. If CRA is correct about the conduct of these taxpayers, they should follow court rules and argue the me...

Inflation Porn

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

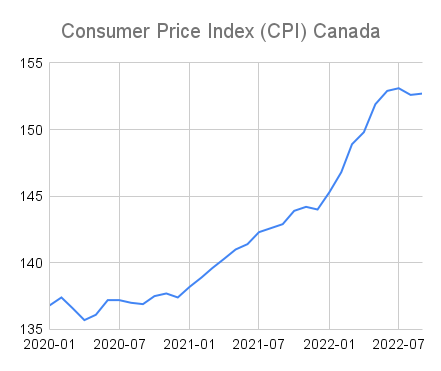

We’ve certainly heard a lot about inflation in the past year or so. Despite the Bank of Canada’s efforts to fight inflation by raising interest rates sharply, we still see headlines blaring that inflation is very high. What’s behind all this? Here is a chart showing the official Consumer Price Index (CPI) for Canada since 2020. We see that inflation was low in 2020, prices rose sharply during 2021 and the first half of 2022, and prices have actually dropped slightly in the past 3 months. However, this is at odds with headlines still screaming that September inflation was still very high at 6.9%. What gives? The answer is that we often measure inflation by comparing current prices (as measured by CPI) to what they were a year ago. So, headlines about September inflation are measuring the change from September 2021 to September 2022. Last month’s headlines focused on August 2021 to August 2022. If it seems like the news is churning out stories wit...

The Inevitable Masquerading as the Unexpected

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Rising interest rates are causing a lot of unhappiness among bond investors, heavily-indebted homeowners, real estate agents, and others who make their livings from home sales. The exact nature of what is happening now was unpredictable, but the fact that interest rates would eventually rise was inevitable. Long-Term Bonds On the bond investing side, I was disappointed that so few prominent financial advisors saw the danger in long-term bonds back in 2020. If all you do is follow historical bond returns, then the recent crash in long-term bonds looks like a black swan, a nasty surprise. However, when 30-year Canadian government bond yields got down to 1.2%, it was obvious that they were a terrible investment if held to maturity. This made it inevitable that whoever was holding these hot potatoes when interest rates rose would get burned. Owning long-term bonds at that time was crazy . One might ask whether we could say the same thing about holding stocks in 2020 ...

Short Takes: Is CPP a Tax?, Credit Card Surcharges, and more

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

A prominent politician recently referred to CPP premiums as a tax. This sparked a debate about this question. Personally, I find CPP premiums look a little like a tax, but mostly not. I once looked into how much of your CPP contributions are really a tax , but this was not intended to be like the current semantic discussion. I don’t think this debate about whether CPP premiums are a tax is very important, but the answer a person argues for can tell you something about what they think about more important questions. Should we scrap CPP? No. Should we be allowed to opt out of CPP? No. Can Canadians do better investing their savings on their own? No. Can most of the people who claim to be able to invest better on their own actually do better? No. Do most of the people who claim to be able to invest better on their own even know their past investment returns? No. Should we reduce CPP premiums to reduce payro...

Short Takes: Investment Signs, Alternative Asset Class Returns, and more

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

I’ve been reading a lot lately about how a recent ruling in Ontario has crushed the hopes for making the designation “Financial Advisor” meaningful. Sadly, this is hardly surprising. The big banks want to be able to call their employees financial advisors. Banks will always be formidable foes, and any designation a bank employee is able to hold is necessarily meaningless. Bank financial advisors may mean well, but they are no match for the carefully constructed banking environment that forces them to sell expensive products to unwary customers. I wrote one post in the past two weeks: Nobody Knows What Will Happen to an Individual Stock Here are some short takes and some weekend reading: Tom Bradley at Steadyhand has an entertaining and important list of investment signs we should look for. Ben Felix and Cameron Passmore come up with estimates of returns for alternative asset classes including private equity, venture capital, angel investing, private credit, hed...

Nobody Knows What Will Happen to an Individual Stock

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

When I’m asked for investment advice and I say “nobody knows what will happen to an individual stock,” I almost always get nodding agreement, but these same people then act as if they know what will happen to their favourite stock. In a recent case, I was asked for advice a year ago by an employee with stock options. At the time I asked if the current value of the options was a lot of money to this person, and if so, I suggested selling some and diversifying. He clearly didn’t want to sell, and he decided that the total amount at stake wasn’t really that much. But what he was really doing was acting as though he had useful insight into the future of his employer’s stock. He proceeded to ask others for advice, clearly looking for a different answer from mine. By continuing to ask others what they thought about the future of his employer’s stock, he was again contradicting his claimed agreement with “nobody knows what will happen to an individual stock.” Fast-forwa...

Short Takes: Microsoft Class Action, New Tontine Products, and more

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

I finally got my $84 from the Microsoft software class action settlement . As I predicted 19 months ago, I had forgotten about this lawsuit, and when the money arrived, it brightened my day (at least until I had to fight with Tangerine’s user interface to figure out how to deposit a paper cheque). I’m not sure why it pleases me so much to get these small sums from class actions, but I’ll keep putting in claims when it’s convenient to do so. Here are some short takes and some weekend reading: Jonathan Chevreau describes Moshe Milevsky’s latest work on tontines to solve the difficult problem of decumulation for retirees. Milevsky says “until now it’s all been academic theory and published books, but I finally managed to convince a (Canadian) company [Guardian Capital] to get behind the idea.” Guardian Capital offers 3 solutions based on Milevsky’s ideas. I’ve complained in the past that academic experts such as Moshe Milevsky and Wade Pfau write about the be...

Short Takes: Portfolio Construction, Switching Advisors, and more

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

I haven’t found much financial writing to recommend lately, and I haven’t written myself, so I thought I’d write on a few topics that are too short for a full-length post. Be ready for anything I sometimes see this advice in portfolio construction: be ready for anything. On one level this makes sense. It’s a good idea to evaluate how it would affect your life if stocks dropped 40% or interest rates rose 5 percentage points. Would you lose your house or would it just be a blip in your long-term plans? However, those who give this advice sometimes use it to mean that you should own some of everything that performs well in some circumstances. So they advocate owning gold, commodities, Bitcoin, and other nonsense along with stocks and bonds. Just because you always own at least one thing that is rising doesn’t mean your overall portfolio will do well. What you want is a portfolio that is destined to do well over the long term, with the caveat that you’ll surviv...

Short Takes: Factor Investing, Delaying CPP and OAS, and more

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

I haven’t written much lately because I’ve become obsessed with a math research problem. I’ve also had an uptick in a useful but strange phenomenon. I often wake up in the morning with a solution to a problem I was thinking about the night before. Sometimes it’s a whole new way to tackle the problem, and sometimes it’s something specific like a realization that some line of software I wrote is wrong. It’s as though the sleeping version of me is much smarter and has to send messages to the waking dullard. Whatever the explanation, it’s been useful for most of my life. Here are some short takes and some weekend reading: Benjamin Felix and Cameron Passmore discuss two interesting topics on their recent Rational Reminder podcast. The first is that they estimate the advantage factor investing has over market cap weighted index investing. They did their calculations based on Dimensional Fund Advisor (DFA) funds used in the way they build client portfolios....

Short Takes: Savings Account Interest, Reverse Mortgages, and more

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

EQ Bank says they’re “excited to announce an increased interest rate!” It’s now 1.65%. Meanwhile, Saven is up to 2.85%. Unfortunately, Saven is only available to Ontarians. It’s normal for banks to offer different rates, but the gap down to EQ is disappointing. Fortunately, the fix is easy; with just a few clicks, my cash savings are mostly in Saven. Here are my posts for the past four weeks: A Failure to Understand Rebalancing Portfolio Projection Assumptions Use and Abuse Here are some short takes and some weekend reading: Jason Heath explains the advantages and disadvantages of reverse mortgages compared to other options. He does a good job of covering the important issues, but doesn’t mention home maintenance. With reverse mortgages, the homeowner is required to maintain the house to a set standard. It’s normal for people’s standards for home maintenance to decline as they age, sometimes drastically when they don’t move well and can’t...

Portfolio Projection Assumptions Use and Abuse

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

FP Canada Standards Council puts out a set of portfolio projection assumption guidelines for financial advisors to use when projecting the future of their clients’ portfolios. The 2022 version of these guidelines appear to be reasonable, but that doesn’t mean they will be used properly. The guidelines contain many figures, but let’s focus on a 60/40 portfolio that is 5% cash, 35% fixed income, 20% Canadian stocks, 30% foreign developed-market stocks, and 10% emerging-market stocks. For this portfolio, the guidelines call for a 5.1% annual return with 2.1% inflation. This works out to a 2.9% real return (after subtracting inflation). We’ve had a spike in inflation recently, but these projections are intended for a longer-term view. The projected 2.9% real return seems sensible enough. Presumably, if inflation stays high, then companies will get higher prices, higher profits, their stock prices will rise, and the 2.9% real return estimate will remain reasona...

A Failure to Understand Rebalancing

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Recently, the Stingy Investor pointed to an article whose title caught my eye: The Academic Failure to Understand Rebalancing , written by mathematician and economist Michael Edesess. He claims that academics get portfolio rebalancing all wrong, and that there’s more money to be made by not rebalancing. Fortunately, his arguments are clear enough that it’s easy to see where his reasoning goes wrong. Edesess’ argument Edesess makes his case against portfolio rebalancing based on a simple hypothetical investment: either your money doubles or gets cut in half based on a coin flip. If you let a dollar ride through 20 iterations of this investment, it could get cut in half as many as 20 times, or it could double as many as 20 times. If you get exactly 10 heads and 10 tails, the doublings and halvings cancel and you’ll be left with just your original dollar. The optimum way to use this investment based on the mathematics behind rebalancing and the Kelly criterion is t...

Short Takes: Dividend Irrelevance, Housing Bears, and more

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

A popular type of investing is factor investing. This means seeking out companies with attributes that performed strongly in the past, such as small caps (low total market capitalization) and value stocks (low price-to-earnings ratios). I can’t say I’ve studied this area extensively, but one observation I’ve made is that these factors always seem to disappoint investors after they become popular. It’s hard to figure out exactly why factors seem to disappoint, but I’m not inclined to pay the extra costs to pursue factor investing beyond my current allocation to stocks that are both small caps and value stocks. Several years ago this combination was my best guess of the factor stocks most likely to outperform. I’m still not inclined to try others. Here is how I think about whether someone is ready for DIY investing: What You Need to Know Before Investing in All-In-One ETFs Here are some short takes and some weekend reading: Ben Felix explains why dividends are irr...

What You Need to Know Before Investing in All-In-One ETFs

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

I get a lot of questions from family and friends about investing. In most cases, these people see the investment world as dark and scary; no matter what advice they get, they’re likely to ask “Is it safe?” They are looking for an easy and safe way to invest their money. These people are often easy targets for high-cost, zero-advice financial companies with their own sales force (called advisors), such as the big banks and certain large companies with offices in many strip malls. An advisor just has to tell these potential clients that everything will be alright and they’ll be relieved to hand their money over. A subset of inexperienced investors could properly handle investing in an all-in-one Exchange-Traded Fund (ETF) if they learned a few basic things. This article is my attempt to put these things together in one place. Index Investing Most people have heard of one or more of the Dow, S&P 500, or the TSX. These are called indexes. They a...

Short Takes: Finding a Good Life, DTC for Type 1 Diabetics, and more

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

I was reminded recently of the paper The Misguided Beliefs of Financial Advisors whose abstract begins “A common view of retail finance is that conflicts of interest contribute to the high cost of advice. Within a large sample of Canadian financial advisors and their clients, however, we show that advisors typically invest personally just as they advise their clients.” I didn’t find this surprising. Retail financial advisors are like workers in a burger chain. I wouldn’t expect these advisors to understand the conflicts of interest in their work any more than I’d expect workers in a burger chain to understand the methods the chains use to draw customers into eating large amounts of unhealthy food. It’s hardly surprising that so many advisors understand little about investing well, and that they run their own portfolios poorly. However, this doesn’t mean the conflicts of interest don’t exist. It is those who run organizations that employ, train, and design pay st...

Measuring Rebalancing Profits and Losses

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Investors often seek to maintain fixed percentage allocations to the various components of their portfolios. This can be as simple as just choosing allocations to stocks and bonds, or it can include target percentages for domestic and foreign stocks and many other sub-categories of investments. Portfolio components will drift away from their target percentages over time, requiring investors to perform trades to rebalance back to the target percentages. A natural question is whether rebalancing produces profits, and if so, how much. A long-time reader, Dan, made the following request: I have a topic request. On the subject of portfolio rebalancing, I have read your many posts and whitepaper [see Calculating My Retirement Glidepath ]. I have actually implemented something similar (but not exactly the same) myself. I saw in one blog post, cannot find where, that you said something to the effect of “my rebalancing trades last year produced a profit”. My topic request...