Posts

Showing posts from March, 2009

There is ample evidence that the average active investor gets lower returns than passive investors, but that doesn’t preclude a minority of active investors from outperforming passive indexes. The great investor and hedge fund manager, George Soros, serves as a hero for the active investor who dreams of outsmarting the market. In his book Soros: The World’s Most Influential Investor , Robert Slater looks at Soros’s life, investing record, philanthropy, and politics. Soros is best known for his 1992 bet against the British pound when the Bank of England was forced to abandon the exchange rate mechanism designed to keep currency values within certain ranges. Soros made about a billion dollars in this high-stakes gamble against the pound and another billion dollars in simultaneous bets on other currencies. Some viewed Soros’s actions as stealing from the British people, but Soros sees himself as a “critic” of financial markets who backs his opinions about the value of stocks and cu...

Understanding Ontario’s Switch to the HST

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Ontario’s 2009 budget included a switch from a retail sales tax separate from the GST to a harmonized sales tax (HST). Superficially, this may seem like a trivial change because the retail sales tax was 8% and the provincial portion of the HST will also be 8%. However, there are two main differences that will affect Ontarians. The first difference is known to most people: the HST will apply to more goods and services than the retail sales tax does. The main change is that services will now be taxed at the 13% HST rate rather than just the 5% GST rate. If this were the only change, then it would represent a substantial tax hike. But, there is another less well understood difference that changes the equation. Businesses can now use input tax credits (ITCs) for the HST. A business that collects HST from its customers doesn’t have to give all this money to the government. The business deducts the HST paid on the products and services it purchases to run its commercial operation...

Help Wanted – Male

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

This is a Sunday feature looking back at selected articles from the early days of this blog before readership had ramped up. Enjoy. I was rooting through my father’s old papers from a time when he was looking for work and came across the following ad that appeared in the July 31, 1964 Montreal Star: I was struck by the obvious sexism and ageism: must be a male between 25 and 35 years old. The point is not to call out this newspaper or the company placing the ad, but to realize that this was an accepted common practice at the time. Slow change can creep up unnoticed, but it’s obvious that the world has changed quite a bit (for the better) since this ad was placed.

Short Takes: Retirement Crisis and Tax Software

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

1. John Bogle, founder of the Vanguard Group, testified before the U.S. House of Representatives about the coming retirement crisis. Bogle makes many strong points about failings of our financial system that threaten retirement. An additional point I’d make is that with people living longer and the retirement age remaining fixed, we are spending in increasing proportion of our lifetimes retired. This seems unsustainable. If life expectancy increases, maybe the retirement age has to increase as well. 2. Canadian Financial DIY rated web tax preparation software . TaxChopper investigated the inconsistent results among different tax packages, and gave a detailed response . 3. Canadian Money Review reports being charged for overpaying a Sears bill! (the web page with this article has disappeared since the time of writing). This is the first I’ve heard of this one. The few times I’ve forgotten to pay a credit card bill on time, I made a big overpayment to avoid ongoing interest c...

Direct Energy Viewed as an Insurance Company

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Direct Energy is well-known for its flat-rate natural gas plans. By guaranteeing rates for a period of time, they are in effect acting as an insurance company. Any time you buy insurance, you need to find out if the other party is financially sound enough to follow through on its promises. According to Direct Energy, they currently offer a two-year flat rate natural gas plan in my area at a rate that is about 30% higher than the variable rate that I’m paying right now. This added 30% amounts to a premium for 2 years of insurance against rate hikes. But what happens if natural gas supplies are interrupted and rates spike up? Will Direct Energy be able to fulfill its promises if variable rates double? I have no idea, but anyone considering entering into a flat rate plan should find out. If Direct Energy isn’t able to maintain promised rates, customers could end up paying the flat-rate premium and then paying the high variable rates too. Any time we enter into agreements with ...

Market Timer Breakeven Date

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

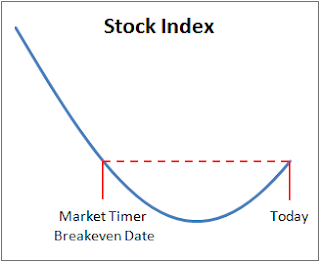

Market timers often jump out of the stock market when they think it is going down in the hopes of getting back in at lower prices. For this to work, the investor has to get out early enough and back in early enough to avoid selling low and buying high. This brings us to the idea of a “market timer breakeven date.” The following picture illustrates what I mean. Let’s assume for the moment that stocks are now on the rise. A market timer getting back into the market today would have to have sold out of the market before the breakeven date shown in the picture to come out ahead. Any given day we can draw a line over to see the new breakeven date. As stocks rise, the breakeven date moves further into the past sweeping by the exit dates of investors who haven’t jumped back in yet making them losers in the market timing game. Of course, the stock market doesn’t move in a nice smooth curve like the one shown. It jumps up and down mostly unpredictably. Looking at the chart of the TSX, the...

Winning the Lottery

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

We’ve all heard that lotteries are a sucker’s game, and this is mostly true. Taking Canada’s Lotto 6/49 as an example, only 47% of the money spent on tickets gets repaid in prizes. So, players pay $2 for a ticket worth only 94 cents. However, there is a way to stack the odds in your favour if you have the right information. There are any number of books and web sites touting systems for picking lottery numbers based on which numbers have been drawn more or less frequently in past draws. None of these work. My system of playing the 6/49 actually has a long-term expectation of profit. To understand this system, we need to start with a little information about how the 6/49 works. Each player chooses any 6 of the numbers from 1 to 49 and pays $2 for this combination. There are just under 14 million combinations available. The draw consists of 6 numbers plus a bonus seventh number. The player gets prizes if his combination matches 3 or more of the drawn numbers. The more matches, ...

Stock Option Friction Revisited

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Last week I showed that the frictional costs of commissions and spreads are higher with stock options than they are with trading stocks . Reader feedback included Mark Wolfinger’s comment that I hadn’t accounted for interest on cash not tied up when investing with options, and Glenn’s comment that option spreads are more reasonable in the U.S. So, let’s do the accounting a little differently and see how it affects the results. The original scenario was to compare direct ownership of 200 shares of RIM to a stock option-based synthetic version of RIM stock ownership where we buy 200 call options at the money and simultaneously sell short 200 put options at the money. This time let’s assume that the market gets the option pricing right to account for the interest on cash that gets tied up with stock ownership but isn’t tied up with the synthetic stock option version. We can calculate the friction costs by simply assuming that each trade loses half the bid-ask spread plus whatever c...

What is a mutual fund?

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

I’m starting a new Sunday feature looking back at selected articles from the early days of this blog before readership had ramped up. Enjoy. Many people own units of mutual funds in retirement savings without knowing much about them. Here’s a little story that is hopefully more useful than the usual dry definition. We are bombarded with messages in ads and from financial planners telling us to buy mutual funds. But, what are mutual funds? It’s a good idea to have a basic understanding of what mutual funds are before ploughing years worth of hard-earned income into them. To start with, let’s go back to a time years ago when there weren’t any mutual funds. An average guy we’ll call Jim heard some good things about the stock market, got curious, and spoke to a stock broker about buying 5 shares of Buggy-Whips-R-Us. The stock broker seemed friendly at first, but when he asked if Jim meant 500 shares, Jim started to feel uncomfortable. The broker went on to explain that his comp...

Short Takes: Bad Tax Software and Model Homes

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

1. Canadian Financial DIY tested all the CRA certified web-based tax preparation packages and found that they didn’t all give the same answers . Apparently certified doesn’t necessarily mean correct. 2. Big Cajun Man tells us some of the pitfalls of buying a model home . 3. Browsing the CRA web site, Preet discovered that the proceeds of crime are taxable .

Stock Option Friction

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Stock options are often demonized as recklessly risky investments. Others tout options as useful tools for managing risk in a portfolio. An aspect of stock options that isn’t discussed much is the frictional costs of commissions and spreads in stock option investing. The people I have known personally who have dabbled in stock options have been burnt badly. They approached options with a gambler’s mentality and lost. This is enough to justify the advice many give to stay away from options unless you are an expert or are getting advice from an expert. On the other hand, if used correctly, stock options can reduce the overall risk in a portfolio. There is no free lunch, though. If the portfolio risk is lower, then the expected return is lower as well. An aspect of stock option investing that has always concerned me is the high friction. Frictional costs are the costs associated with trading in and out of stock or option positions. When I buy or sell stocks or ETFs, I pay a visible...

Economic Disaster is upon Us

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

The media are bombarding us with comparisons between the current recession and the great depression. Many reporters try hard to find economic measures that make our current situation seem worse than the depression. Stock market losses over the past 9 months are one area where we seem worse off than those who experienced the losses in 1929. While Canadian stocks as measured by the TSX dropped to 5 and a half year lows last week, U.S. stocks as measured by the S&P 500 dropped to 12-year lows. So, U.S. stocks prices are at levels not seen since 1997. And we all know what a stink-hole the world was back in 1997. Giant worms roamed the streets killing people. No, that was a bad movie I saw. Actually, 1997 was pretty good for me. I enjoyed my job, played sports, and had a loving young family. Life was good even without an iPod. Current circumstances are no fun for those who have lost their jobs, but it’s hard to compare the inconvenience of having to take a lower paying job...

Collision Insurance on Cars

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Until recently, I hadn’t thought much about the collision part of my car insurance. When my car insurance renewal papers arrived, I puzzled over them for a while trying to see if there was any way to reduce the premium. To figure out whether it’s worthwhile to carry collision insurance, you have to know how much the insurance company will pay in the event of an accident. You’ll never get more than the write-off value of the car. Even though you might not want to get a new car, the insurance company won’t fix a car if the repairs cost more than they think the car is worth. My car is getting older, and based on what the insurance company representative told me on the phone, my best guess of its write-off value is about $5000. I also have a $2000 deductible, and so the most the insurance company would ever pay me for my car is $3000. The fact that it is worth more than this to me is irrelevant. For this $3000 of coverage I would have to pay $309. I doubt that the odds of writing off...

Income Tax Takes Time

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

For people who like to optimize and are expecting an income tax refund, we are now into income tax filing season. For those who will have to pay more, tax filing season won’t come until the end of April for Canadians and April 15th for Americans. Ordinarily I prepare my taxes a little at a time until I finally receive the last slip I need and then e-file my return to get the refund as soon as possible. This year I decided to see how long it would take to complete the full task of filing my taxes. So, I didn’t do any advance work beyond storing slips and receipts in appropriate folders. One day when I was satisfied that I had all the required information, I started working on the taxes for myself and my wife at 1:00 pm. This began with buying a copy of QuickTax online and installing it. My reason for using QuickTax is mostly momentum. I know how to use it, and haven’t seriously tried other options. It’s amazing how some tasks always seem to take longer than they should. I didn’t ...

Short Takes: Tax Tips and Doing a Good Job

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

1. Since Monday’s close, the TSX jumped 9.5% in three days. There is no guarantee that these gains won’t disappear, but if this turns out to be the beginning of a sustained recovery in stock prices, it would be interesting to know how many market timers missed this jump while trying to predict the market bottom. 2. Big Cajun Man has tax tips for parents of university students . 3. Preet describes some experiments to determine what motivates people to do a good job .

Nortel vs. Beer

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

I offer the following story with apologies to Dean Staff who appears to be the author of the original version. Big Ted lived a full life and died in the year 2000, leaving only $10,000 to be split equally between his sons Ted Junior and Tim. Tim took his $5000 and immediately invested in the hot stock of the day, Nortel. After paying the sales commission, he got 40 shares. Ted Junior was more like his father and decided to spend his money on a huge party for his friends. Ted’s $5000 paid for 166 cases of beer that was all consumed in a huge bash. It took a week to clean up after this party. Ted piled all the empties in the back of his garage and forgot about them for a long time. A month ago, Ted decided to clean out his garage. A few of his friends who had partied with him over 8 years earlier helped bring all the empties back to the beer store. There was surprisingly little breakage, and Ted got back enough from the empties to buy 13 more cases of beer for another smalle...

What Does DIY Investing Mean?

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Do-it-yourself (DIY) investing means different things to different people. When experts list potential pitfalls of the DIY approach, the message can be misleading depending on what DIY investing means to the reader. An investor who investigates companies and chooses individual stocks to buy is clearly a DIYer. At the other extreme we have someone who hands control of his portfolio to an investment advisor who gets paid a substantial portion of the portfolio each year. This type of investor is clearly not a DIYer. A gray area is the index investor. In one sense, index investors are DIYers because they aren’t paying for investment advice. On the other hand, they don’t choose their own individual stocks and bonds, which makes them seem less like DIYers. For the index investor who doesn’t engage in market timing, the standard list of DIY investing pitfalls doesn’t apply. Beyond an initial decision of which indexes to buy and in what proportions, index investing takes very little ...

Mind Games to Control Spending

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Between job losses and investment losses, many of us have a need to reduce spending. However, when it comes to maintaining lifestyles, momentum is difficult to overcome. Adjusting the way you think about wealth might help. Sometimes a big price increase can jolt us out of an expensive habit. People who lose their jobs often keep paying for ultra cable TV service, but what if its price suddenly rose 50% or more? Even people with healthy finances might drop down to a lesser cable package in the face of a big price increase. This brings me to the mind game. What if we stopped measuring wealth in dollars and instead measured it in units of our favourite index ETF, like XIU for example. XIU holds stock in the biggest businesses in Canada. Each unit represents a slice of various big companies, which includes real estate and many other valuable assets. In contrast, money is just pieces of paper, bits of metal, and electronic data that have very little inherent value. A unit of XIU has...

Compact Fluorescent Lights Save Less than Many Believe

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

I saw a piece on CBC Newsworld saying that compact fluorescent lamps (CFLs) don’t save as much money as many people claim. The piece made the explanation seem mysterious and complicated, but it’s quite simple. The problem with the standard analysis is that it ignores secondary effects. The relevant secondary effect here is heating. All energy absorbed by a light bulb ultimately turns into heat. Even the light produced will bounce around off objects and eventually turn into heat. So a light bulb inside your house is like a mini electric heater. A tiny fraction of the light might escape through a window, but for practical purposes, 100% of the energy heats your home. Here’s an example of the standard analysis of savings. Suppose that you replace a 60-Watt incandescent light bulb that gets used 6 hours per day with a 15-Watt CFL. Power consumption drops by 45 Watts for 6 hours per day. This saves a total of 8.2 kilowatt-hours per month. Assuming a cost of 12 cents per kilowatt-h...

Short Takes: Emotional Investing, “the Grid”, and more

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

1. Jason Zweig at the Wall Street Journal has some ideas to allow you to get a feeling of control over your investments . Investors often make big mistakes when their react emotionally. Zweig’s suggestions may help investors deal with their emotional side. 2. Preet explains how financial advisor behaviour is driven by a compensation grid . 3. Potato tells us that Petro Canada Mobility is jacking up its rates for cell phone air time . In addition to increasing the cost of air time, they are increasing the minimum deposit from $20 every 6 months to $25 every 4 months, an 87.5% increase. I have a cheap Petro Canada cell phone mainly because I use it so little that the minimum deposit is relevant to me. Thanks for the warning, Potato. I’ll be getting rid of this phone if I can find a better deal. 4. The Big Cajun Man dug into his archives for the story of how he made allowances for his kids work for his family .

A Thousand-Foot View of the Credit Crisis

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Big changes are taking place in the world economy due to the shock of the credit crisis. These changes have come on too quickly and severely, but the changes themselves aren’t all bad. For this discussion it’s convenient to think of all people as being either spenders or savers ( as I did once before ). Spenders borrow from savers for consumption, and savers lend to spenders with the promise of getting paid back with interest. It turns out that the promised levels of interest on borrowed money were illusory. Spenders are defaulting on loans, and savers are eating the losses. Even when bad debts are covered by the government, this amounts to a flow of money from savers to cover the bad debts. During the long period leading up to the credit crisis, spenders were being permitted to consume more than their fair share of resources. The world economy adapted to this situation by producing goods and services consumed by spenders. The world produced too much clothing for shopping a...

Buffett’s Solution for Mortgage Abuses

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

In his 2008 letter to shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway , Warren Buffet offers his solution for preventing a repeat of the mortgage crisis. His ideas are quite reasonable, but governments may not like them much. It’s hard to improve on Buffett’s explanations. So, I’ve reproduced his summary of the crisis, real reason why foreclosures happen, and his proposed solution. As sensible as his solution is, political interference very likely would undermine it. Summary of the mortgage crisis: “The need for meaningful down payments was frequently ignored. Sometimes fakery was involved. (“That certainly looks like a $2,000 cat to me” says the salesman who will receive a $3,000 commission if the loan goes through.) Moreover, impossible-to-meet monthly payments were being agreed to by borrowers who signed up because they had nothing to lose. The resulting mortgages were usually packaged (“securitized”) and sold by Wall Street firms to unsuspecting investors. This chain of folly had to end badl...

Madoff Wants to Keep $62 Million

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Bernard Madoff’s lawyers are arguing that a Manhattan apartment and $62 million are unrelated to the fraud investigation because they are in his wife’s name. Nothing ventured, nothing gained I suppose, but this one doesn’t pass the sniff test. It’s hard to wrap my mind around the extent of the crime here. Madoff is accused of a $50 billion fraud. That would be like committing a $1 million fraud once a day for over 130 years! The idea that he could come out of this with anything more than some worn personal items in a suitcase sickens me. It will be interesting to see whether the legal system is able to give Madoff any kind of meaningful punishment. One thing that seems certain is that the process will take a long time.

Buffett’s Justification of Option Trading Misses the Mark

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

I disagree with Warren Buffett on a point about his stock option trading. There, I said it (or wrote it). It’s rare that I disagree with anything Buffett writes. In fairness, it’s not that I think he made a poor investment. It’s just that I think the real explanation of why his investment is a good one is different from his justification. Buffett’s eagerly anticipated 2008 letter to shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway arrived on Saturday. It contains his usual brilliant financial insights expressed clearly. Any number of reporters will summarize its contents, but those interested should consider reading the original letter as well. One aspect of the letter that caught my attention was the discussion of Buffet’s option trading. He believes that certain long-term put options are mispriced, but his explanation of why they are mispriced leaves out the dominant reason. Buffett has sold put contracts on the world’s major stock indices. These contracts amount to bets between B...

Archive

Archive

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- George Soros: Hero for the Active Investor

- Understanding Ontario’s Switch to the HST

- Help Wanted – Male

- Short Takes: Retirement Crisis and Tax Software

- Direct Energy Viewed as an Insurance Company

- Market Timer Breakeven Date

- Winning the Lottery

- Stock Option Friction Revisited

- What is a mutual fund?

- Short Takes: Bad Tax Software and Model Homes

- Stock Option Friction

- Economic Disaster is upon Us

- Collision Insurance on Cars

- Income Tax Takes Time

- Short Takes: Tax Tips and Doing a Good Job

- Nortel vs. Beer

- What Does DIY Investing Mean?

- Mind Games to Control Spending

- Compact Fluorescent Lights Save Less than Many Bel...

- Short Takes: Emotional Investing, “the Grid”, and ...

- A Thousand-Foot View of the Credit Crisis

- Buffett’s Solution for Mortgage Abuses

- Madoff Wants to Keep $62 Million

- Buffett’s Justification of Option Trading Misses t...

-

-

-